History moves in circles – or rather a square, if you go according to Samuel Moaz new film ‚Foxtrot‘, that follows the traumatic impact of war and more everyday tragedies on a family in modern-day Israel. The square, that the steps of the foxtrot trace on the floor, become a symbol for how psychological wounds get handed down the generations. From a survivor of the holocaust, to her accomplished son that hides the darkness of the Lebanon war and has never talked about his experiences. Not even to his wife and certainly not to his son, who now has to serve as a soldier himself on a remote checkpoint in the middle of nowhere. It’s forward, forward, sidestep, back, back, sidestep, forward, forward, sidestep…

The Friedmans are an atheist family in modern-day Israel. Two Parents, Michael and Daphna one son, Jonathan, and one daughter, Alma. A well-to-do family, living in an ecclectic apartment in Tel Aviv. When three young soldiers come to tell the parents of their sons death, cuts and scars open again that have been buried for some time. The film intimately follows the father descending into grief: his attempt to tell his mother, who remains cold and distant, then into the funeral arrangements, that are dictated by a fanatical officer that frowns at the lifestyle of the Friedmans. When the father demands to see the body of his son, his paranoia deepens. Nobody can tell him where the body is or if there even is a body. He is patronized for his worries and turns violent, but suddenly the soldiers come back: „There’s been a mistake. Your son isn’t dead.“ The father, who has tried to keep it together, blacks out.

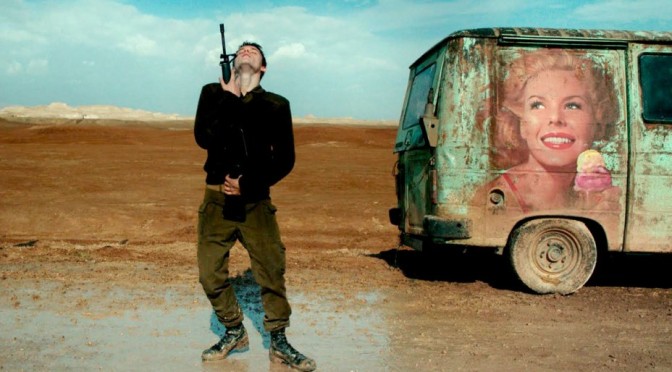

The story moves to a remote check point in the middle of the desert, where Jonathan is bored to death and miserable. The futility and repetitiveness of their task impacts him and his three fellow soldiers as they try to alleviate their boredom with stories from their childhood. The container they live in seems to be sinking into the mud a bit more each day, out of date technology is used to check on the people moving through, who’s humiliation is simply a part of the process. Eventually tragedy strikes in a first beautiful and then frankly terrible moment. Jonathan, the viewer realizes, will never be the same. The officer that arrives soon after to bury the case quite literally in the ground approaches with shiny boots and leaves with them drenched in the mud of a real-life war that isn’t fought from the tower of ideology. Still, he receives a call during his visit and sends Jonathan home to his parents.

Back in Tel Aviv the mother prepares a cake, her hands are shivering. She is arranging a 29 out of pomegranade seeds. Strange, because nothing is alright. Jonathan is dead. Again? What has happened? The couple tries to come to terms with this death and their own failings. It’s brutal in a way what they drag up from their memories and present, a brutality only two people living together for more than twenty years can achieve. Still there is some memories they remember fondly, so they smoke some weed they have found in their sons things. And their daughter Alma is also there with her everyday life and teenage worries.

The last scene of the movie finally answers the question that was in the background of the third act. Why has Jonathan died, when he was already on his way home, to safety? It reveals that there are two kinds of tragedies in ‚Foxtrot‘. One is the systematic cruelty of a country in a constant state of low-key war, that perpetuates a trauma of violence generations old. The other is a camel standing on the road in front of you. Isn’t life already cruel enough? Why make it even crueler with war?

Foxtrot is arranged very well, moving from one act to the next and weaving a tight net of symbolism and metaphor, that doesn’t interfere with the strong emotional realism of the characters. A strong cast of actors strengthens the script with Lior Ashkenazi and Sarah Adler as the parents, while Yonathan Shiray plays their son Jonathan. The director who has won the Golden Lion with his film ‚Lebanon‘ in 2009 returns to his subject matter and seems to have made a kind of sequel. The only distraction are the sometimes obvious sets, that are well designed and made, but still keep clashing with the emotional involvement in the story. An aesthetic that moves the movie a bit more towards fable and makes an example out of the characters.

Interestingly ‚Foxtrot‘ is the most recognized of quiet a few movies about middle-eastern conflict and life at the Venice Film Festival. Tzahi Grads ‚The Cousin‘ and ‚The Insult‘ by lebanese director Ziad Doueri are both in the programme, as well as others.

The picture for this article was obtained through La Biennale di Vinezia and doesn’t belong to the authors.